January 11, 2022

After a year researching the impact of the pandemic and the disruption to learning among pupils in England, Renaissance and Education Policy Institute (EPI) have published two new reports as part of our joint research project commissioned by the Department for Education. .

For many students worldwide, the 2020/2021 academic year delivered unprecedented challenges and, in many cases, worsened the learning gaps that already existed before the Covid pandemic.

These two releases build on our previous research with findings from the Spring and Summer terms of 2021, providing an overall estimation of the impact of the pandemic on student outcomes in the 2020/2021 academic year. As before, this research is based on our Star Reading and Star Maths assessment data for pupils in England from the past 4 years.

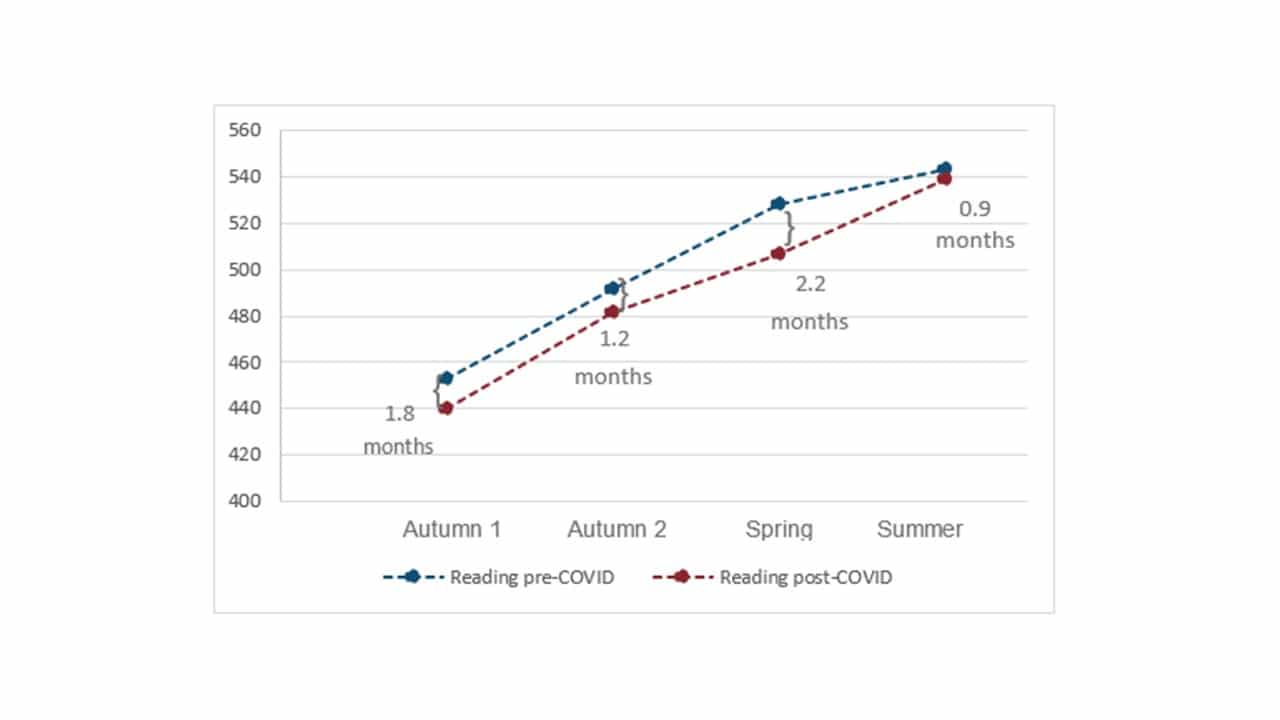

Throughout this blog post, as well as in the research itself, we comment on the “learning loss.’’ When we use the term “learning loss” what we actually mean is, the difference between where pupils are as a result of the pandemic, compared to where we would expect them to be in a typical, pre-pandemic school year, based on 2 years of historic data and progress trends. This is shown both in months and Renaissance Scaled Score with breakdowns by demographics and region, allowing for the different progress rates within these sub-groups to be taken into account. We of course appreciate that students cannot lose what they never learnt, and so although this term is used throughout, it may be better to think of it as missed learning.

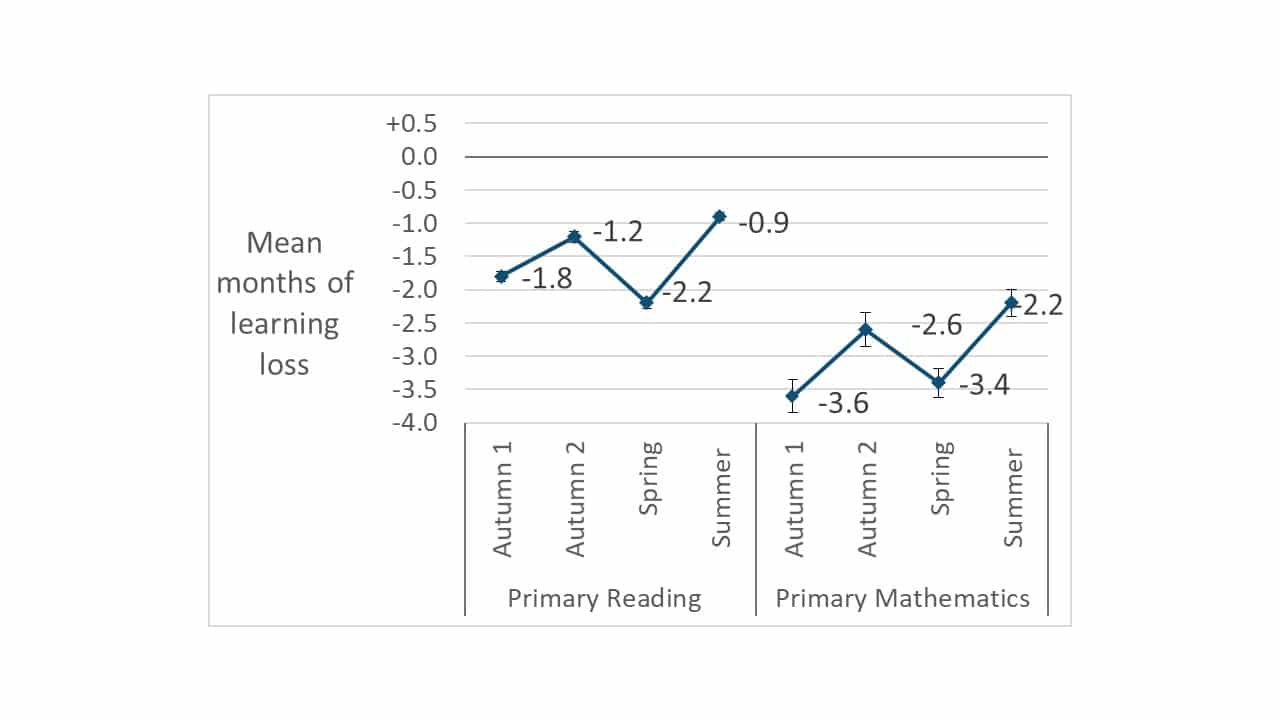

Key findings from the Spring and Summer reports include:

- Pupil learning losses were reduced by around a month after the return to schools in the summer term, but pupils still suffered substantial losses, particularly disadvantaged pupils and those in deprived areas.

- Pupils in parts of the north of England and the Midlands saw greater learning losses than those living in other regions.

- Disadvantaged secondary school pupils seem to be the most impacted, having fallen even further behind by the 2021 Summer term compared to where they were in the Autumn term.

- It is estimated that losses experienced by disadvantaged pupils during the pandemic are the equivalent of undoing a third of the progress made over the last decade in narrowing the attainment gap in education.

- There is an association between the level of pupil absence and the extent of learning losses- the more time pupils spent in school when schools re-opened, the smaller the degree of learning loss.

What was the picture across the 2020/21 academic year?

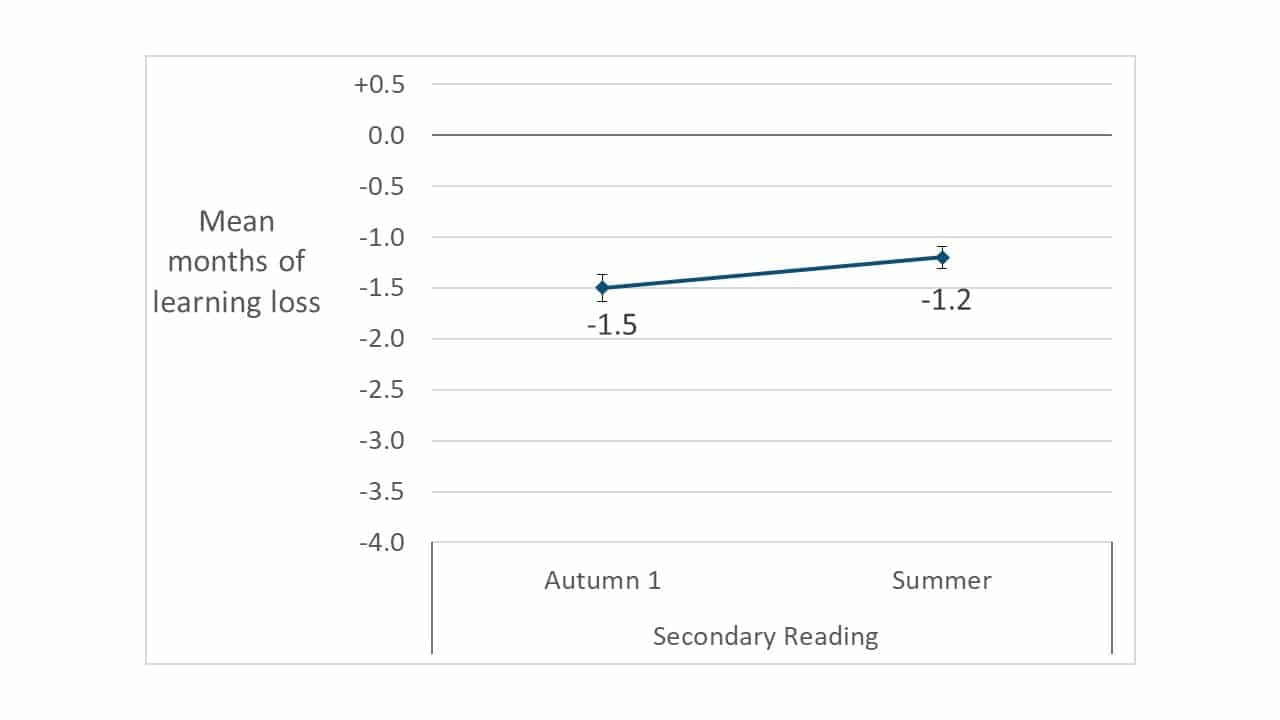

When we look at the year as a whole, it is clear that periods of school closure had a significant impact on student outcomes. However, when schools were fully re-opened for in-person learning across the Autumn and Summer terms, we see encouraging signs of recovery, highlighting the resilience of students and the efforts of schools and teachers. As a result, the gap between actual outcomes in 2020/21 and expected outcomes reduced by the end of the school year for primary reading and maths, and for secondary reading.

However, it is of note that secondary school pupils did not recover as much as primary pupils in reading. In fact, secondary pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds (defined as pupils eligible for free school meals at any point in the last six years) lost almost 2 months more than their peers from more affluent backgrounds; ending the school year 2.4 months behind expected, compared with 0.9 months behind in the Autumn term. Non-disadvantaged students on the other hand were 1.3 months behind in the Autumn term and only 0.8 months by the end of the year.

It is also important to acknowledge that the ‘0.0’ in the above graphs are not static points, but instead indicate the expected outcome at that point in the year. The graph below helps to illustrate this as we see that pupils were still making progress in their learning during the pandemic, it’s just that this was at a lower rate than expected in a normal year based on historic progress trends.

What is new in these releases?

As well as continuing to explore the impact of the learning disruption on student outcomes, for the first time, these releases also explore the link between area-level and pupil-level deprivation, as well as between pupil absence (despite schools being open for in-person learning) and higher learning losses.

- Regional variation in learning losses

Our previous research found significant regional variation, and this remains the case in the Spring and Summer findings. What’s more, when an indicator of area-level deprivation (IDACI)1 was added in, we see that pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds, but also those from non-disadvantaged backgrounds but living in deprived areas, are adversely affected in both reading and maths.

By the end of the year, we find that:

- Pupils in the Midlands and the North-West saw the greatest learning losses in primary reading, with Yorkshire and the Humber and the West Midlands most affected at secondary. Pupils living in London and the South of England saw the smallest impact in reading.2

- In primary mathematics, the differences between regions seem to be larger, with pupils in the East of England, parts of the North and the East Midlands seeing the largest impact and those in the South-West seeing the smallest.

- In all instances, non-disadvantaged pupils living in areas with higher levels of deprivation were more impacted than those living in areas with lower levels of deprivation.

- These non-disadvantaged pupils living in areas with a high level of deprivation actually saw similar or higher levels of learning loss compared to disadvantaged pupils living in areas with a low level of deprivation. This affect was strongest in primary maths where non-Ever 6 FSM pupils in an area with high levels of deprivation saw learning losses of 3.1 months compared with 1.6 months for Ever 6 FSM pupils living in an area with low levels of deprivation.

2. The relationship between school absence and learning loss

Finally, the research also found a correlation between learning loss and the amount of time pupils were absent from school during periods when schools were fully open. It is cautioned, however, that this is not necessarily causation as there are other factors often linked with absence, such as disadvantage, less engagement with school, lower parental involvement or extenuating medical circumstances, which could all be playing a role.

Absence data was available at pupil-level in the Autumn term and school-level for the Autumn and Spring terms. Overall, we find that:

- In the Spring term, primary aged pupils with a low level of absence in their schools experienced learning loss of 2 months in reading. This rises to 2.9 and 3.2 months respectively for pupils with a medium and high level of absence in their schools.

- For secondary reading in Spring, the picture wasn’t as stark with losses of 2.4, 2.6 and 2.4 months respectively. However, pupil-level absence in the Autumn term for secondary pupils showed a difference between 1 month and 5.1 months learnings loss for reading between the lowest and highest rates of absence.

- For primary maths in the Spring term, schools with a low level of pupil absence saw average learning losses of 3.2 months, compared to losses of 4.7 months for schools with a high level of pupil absence.

New Benchmarks for Star users

If you read our previous blog post, you will know that users of Star Reading and Star Maths can use this research to benchmark their own pupils and get a much needed insight into how your school has fared compared to the national picture following two years with no national outcome data. These two releases add benchmark Scaled Scores for Spring 2 and the Summer term to aid your analysis. As our Star data was matched with the National Pupil Database, these benchmarks are available at various subgroup breakdowns so you can compare like with like.

So, what can we learn from these findings?

In summary, the story of the 2020/21 academic year was one of recovery and missed learning with a pattern aligned to the level of disruption faced by schools and pupils due to the pandemic. This pattern and the difference between the expected and actual outcomes across the year was affected by multiple, intersecting factors, including the proportion of days pupils were absent from school, area level deprivation across the country, regional differences and demographic differences, as well as the differential rates of progress and historic prior attainment in each of these sub-groups.

The granularity offered by this research provides numerous insights and, in many cases raises more questions which we hope to continue to explore. It is also important, however, to be aware of its limitations. This research only looks at reading and maths attainment, and only for students in England who were in Years 3-9 during the 2020/21 academic year. It is assumed that the impact for younger pupils will be even greater due to the impact on their most formative years and we are very aware that these aggregates may not align with the reality on the ground for schools. Data can only get us so far, as of course, every school and student will be affected differently.

However, what this research does offer is the most robust and granular insight into the impact of Covid on reading and maths so far and provides a much-needed resource and benchmark for school leaders in the absence of any comparable national outcomes. As we all continue to navigate the pandemic, further disruption to learning continues and we will be releasing a final report in this series to look at the reality from the first half-term of 2021/22 to continue to measure the variable impact on pupils in England.

It is our mission at Renaissance to accelerate learning for all and we will continue to support schools as they work through this most challenging of periods. With pressures from staff and student absences, it may help to focus time and energy on the children most affected and the skills which will be most impactful. Star Assessments diagnostic reporting and inbuilt Focus Skills™ highlight the skills which children are ready to learn next and identify the prerequisite skills which will have the quickest impact on their learning. You can learn more about these critical skills and how to put them into practice in this blog.

If you would like any further support interpreting this research or benchmarking it against your own data, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.